De Vaquero to Cowboy Pt. 7: The Vaquero Legacy Today—How Spanish Roots Still Shape the American West

NOTE: This is part 7 of 7 in this series. For part 1, visit HERE.

The West You See Is Built on Spanish Foundations

If you visit a working ranch in Texas, California, or the Southwest today, you're stepping into a landscape that's been shaped by 500 years of vaquero tradition. The equipment hanging in the barn, the techniques the cowboys use, the words they speak, the events they attend—it's all built on foundations laid by vaqueros centuries ago.

The remarkable thing is that most people don't realize they're witnessing living history. They see a modern cowboy and assume everything about that person and that culture is authentically "American" in origin. But if you know what to look for, you can see the Spanish influence everywhere.

This episode is about recognizing that influence. It's about understanding that the American West isn't a story that started in the 1800s with Anglo-American settlers. It's a story that includes 300 years of Spanish colonization and vaquero culture before Americans ever arrived. And that earlier story is still alive today—still shaping how ranches work, how rodeos function, how Western culture understands itself.

Modern Ranching: The Techniques That Never Changed

Walk onto a working cattle ranch today, and you'll see cowboys performing the exact techniques that vaqueros perfected centuries ago. The methods have been refined, adjusted for modern equipment and scale, but the core skills remain unchanged.

A modern cowboy roping a steer uses the same fundamental technique as a vaquero in 1850s California. He throws a loop using the vaquero method—timing the throw with the horse's stride, building a small loop rather than a large overhead spin. He dallies the rope around the saddle horn when the steer is caught, distributing the force the same way vaqueros learned to do it. He reads the steer's movement, anticipates its direction, and adjusts his horse's position using the same understanding of animal behavior that vaquero tradition encoded.

The saddle he sits in is still fundamentally a vaquero saddle design, even if modern manufacturers have added cushioning and comfort features. The horn is still there because it's essential to dallying. The stirrups are still positioned for the same kind of leverage and mobility that vaqueros required. The weight distribution still reflects 300 years of vaquero engineering.

The gear hanging in the barn—the lariats, the chaps, the spurs—these are all direct descendants of vaquero equipment. Some are manufactured by modern companies with sleek marketing and updated materials. Some are still made by craftspeople using methods that haven't changed much in decades. Either way, they're recognizably the same tools.

Rodeos: Where Vaquero Tradition Became American Spectacle

Modern rodeos are direct descendants of the rodeos that vaqueros organized in Spanish Mexico and Mexican California. But the transformation from practical work event to entertainment spectacle tells a fascinating story about how cultures adopt and adapt traditions.

The early rodeos—the ones vaqueros created—were practical gatherings. Ranches needed to round up cattle. Neighboring vaqueros would come together to help. These gatherings naturally evolved into competitions where vaqueros could test their skills against each other. Racing, roping, riding—all these events grew out of actual ranch work.

When Americans encountered these gatherings in the 1870s and 1880s, they recognized the entertainment value. Buffalo Bill Cody incorporated rodeo events into his Wild West shows. Local communities began organizing rodeos as public events. By the early 1900s, rodeos had become formalized competitions with rules, prizes, and paying audiences.

But here's what's interesting: the actual events in modern rodeos still reflect the original vaquero activities. Roping events in modern rodeos use techniques perfected by vaqueros. Bronc riding—the event where a cowboy rides an untamed horse—recreates the essential skill that vaqueros needed to break wild horses. Steer wrestling (where a cowboy jumps from a horse onto a steer and wrestles it to the ground) is adapted from techniques vaqueros used in practical ranch work.

The venues have changed. The audience has changed. The stakes (prize money instead of practical necessity) have changed. But the core activities remain rooted in vaquero tradition. When you watch a modern rodeo, you're watching a tradition that's been adapted for entertainment, but you're still seeing vaquero skills on display.

Regional Ranching Styles: The Spanish West vs. Everything Else

One of the most visible ways vaquero culture continues to shape the American West is through regional ranching styles. The Southwest—particularly California, Texas, and the border regions—has developed distinctive ranching practices that are clearly rooted in vaquero tradition. These regions look, sound, and operate differently from ranching regions that developed without that Spanish foundation.

In California, for example, the ranching culture that developed around the Gold Rush era was shaped directly by interaction with Mexican vaqueros. The saddles, the equipment, the vocabulary, the techniques—all of these reflect that Spanish influence. California ranching developed as a synthesis of vaquero tradition and American entrepreneurship.

Compare this to ranching regions that developed in areas without established vaquero culture. In parts of the Great Plains, ranching developed with less direct influence from Spanish tradition. The techniques evolved differently. The equipment looked different. The vocabulary was different.

This creates regional differences that are still visible today. A working ranch in south Texas operates differently than a ranch in Montana, not because of different geography or cattle breeds, but because of different historical cultural foundations. The Texas ranch inherited vaquero tradition. The Montana ranch often didn't.

The Rodeo Circuit: Professional Western Culture Today

The modern professional rodeo circuit—with major events like the Pendleton Round-Up, the Calgary Stampede, and the National Finals Rodeo—is built on vaquero competitive traditions. These are big-money professional events where athletes (and yes, rodeo competitors are athletes) compete at the highest levels of their disciplines.

The skill required to compete successfully in modern rodeo events is legitimately impressive. A professional roper can throw an accurate loop at full gallop on a moving target. A bronc rider can stay mounted on a horse that's doing everything possible to throw him off. These are difficult, dangerous skills that take years to develop.

And these skills trace directly back to vaquero tradition. A professional roper today is executing techniques that were perfected over centuries. A bronc rider today is performing a feat that vaqueros needed to accomplish as part of regular ranch work.

One interesting modern development: rodeo has become increasingly professionalized and commercialized. This is different from vaquero tradition, where the skills were means to an end (managing cattle efficiently). In modern rodeo, the skills have become ends in themselves—the point is to perform the skill at the highest level for competition and prize money.

But the skills themselves haven't changed. The techniques are the same. The equipment is the same (or very similar). A vaquero from the 1850s, dropped into a modern rodeo arena, would recognize every activity and could probably explain how to do it better than most modern competitors.

Popular Blog Posts:

Western Gear and Fashion: The Visible Legacy

Walk into any Western wear store, and you're in a temple to vaquero-influenced fashion. The styles—the hats, the boots, the spurs, the belts—these are rooted in vaquero practical wear that got romanticized and commercialized.

The Stetson cowboy hat, for example, was influenced by Mexican and vaquero hat styles. Western boots developed from vaquero riding boots. Spurs are direct descendants of vaquero spurs. Western belts with large decorative buckles evolved from practical vaquero belts with functional buckles for carrying gear.

What's interesting is that this gear was originally designed for function, not fashion. A vaquero wore chaps because they protected your legs from chaparral thorns, not because they looked cool. He wore spurs because they provided precise control signals to the horse, not because they looked impressive. The hat protected him from the sun and rain, not because it made a statement.

But as vaquero culture was romanticized and commercialized in American culture, these functional items became fashion statements. Today, someone might wear Western wear not because they work on a ranch but because it looks like a certain kind of cool. The functional items have become symbolic.

The public visibility of this gear is remarkable. Western wear is recognizable and iconic. The image of a cowboy in a hat, chaps, and spurs is so strongly embedded in American culture that it's basically a symbol of the American West itself. And that symbol is built on vaquero practical wear that traveled north through cultural contact and then got absorbed into broader American identity.

Horse Breeds and Ranching Stock: The Spanish Horse Legacy

Modern ranch horses in the American West are often descended from Spanish horses—horses that were brought to the Americas by conquistadors and settlers, and that were then developed and refined by vaqueros over centuries.

The Quarter Horse, one of the most common ranch horses in America, was developed through selective breeding that reflected vaquero needs and preferences. Quarter Horses are quick, agile, and strong—exactly the characteristics that vaqueros valued in a working horse. The breed became standardized in the American West through ranching practice and selective breeding.

Similarly, cattle breeds used in the Southwest reflect Spanish colonial introduction of cattle to the Americas. The Longhorn cattle that became iconic in Texas ranching are descended from Spanish colonial cattle herds. These weren't breeds that Americans developed—they were breeds that existed in Spanish America and that Americans inherited when they took over ranching operations.

This means that even the animals being worked with on modern ranches are part of the vaquero legacy. The horses have been refined through American breeding programs, but they carry genetic heritage from Spanish colonial stock. The cattle have been selectively bred for different purposes than vaquero ranching required, but they're descended from Spanish cattle.

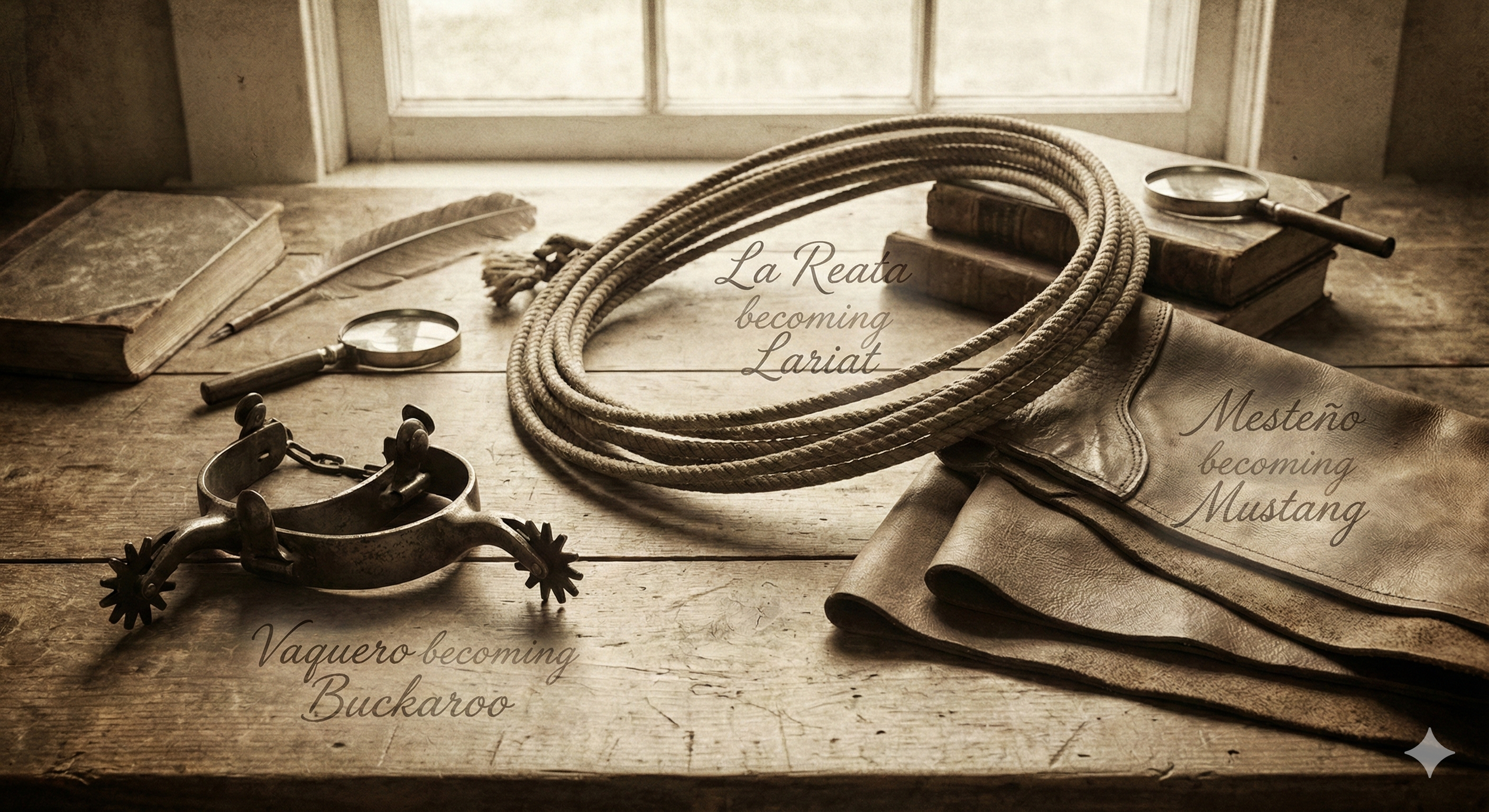

The Vocabulary of Modern Ranching: Spanish Words We Don't Notice

Modern ranch workers and rodeo competitors speak English, but their vocabulary is loaded with Spanish-origin words that we discussed in Episode 6. These words aren't relics of the past—they're actively used in contemporary ranching culture.

A modern cowboy talks about saddling up a bronco, throwing a lariat, dallying the rope, working the remuda, and wearing chaps. These aren't old-fashioned terms—they're standard contemporary vocabulary in ranching communities. The words are actively preserved because the work is actively preserved. People keep using the Spanish words because they're the most precise terms for the specific activities.

This is one of the ways vaquero culture stays alive in American ranching: through the vocabulary. The words carry the history along with them. Every time a modern cowboy uses a Spanish-origin word, he's preserving vaquero linguistic tradition, usually without thinking about it.

Cultural Pride and Identity: What Vaquero Heritage Means Today

In regions with strong vaquero heritage—particularly south Texas, southern California, and border regions—vaquero culture is an important part of regional identity. People take pride in vaquero traditions. Regional ranching styles are celebrated and preserved. The cultural heritage is recognized and valued.

Some communities have vaquero heritage organizations, cultural events, and educational programs dedicated to preserving and teaching vaquero traditions. These communities explicitly recognize that their ranching culture is built on Spanish and Mexican vaquero foundations.

In other regions, vaquero heritage is less explicitly acknowledged. But it's still there, still shaping ranching practices and Western cultural identity, even if people don't consciously think about it.

The Challenge of Recognition: Giving Credit Where It's Due

One of the ongoing issues with vaquero legacy is proper recognition and credit. Ranching traditions that are directly descended from vaquero practice sometimes get presented as purely American innovations. The Spanish and Mexican roots get minimized or forgotten.

This has been changing in recent years. Historical scholarship has become more careful about tracing cultural origins. Cultural institutions in regions with strong vaquero heritage have become more explicit about acknowledging Spanish and Mexican contributions to American ranching culture.

But the broader American cultural narrative about the West still often centers on Anglo-American settlers and entrepreneurs, with vaquero and Mexican contributions as a secondary element rather than a foundational one. The practical value of understanding vaquero legacy is that you can recognize and appreciate the fuller story of how the American West developed.

The Living Tradition: Vaquero Culture Continues to Evolve

It's important to recognize that vaquero culture isn't a static historical artifact. It's a living tradition that continues to evolve. Modern vaqueros and cowboys adapt techniques, equipment, and practices to contemporary conditions while maintaining connections to traditional methods.

A modern ranch might use GPS to track cattle instead of riding to find them. But when the GPS technology fails, or when you need to work cattle in rough terrain that vehicles can't navigate, the same roping and riding techniques that vaqueros perfected centuries ago are still the most effective solution.

A modern rancher might use modern saddles with synthetic materials instead of leather. But the design still reflects vaquero engineering principles because those principles solved real problems that still exist today.

This is how traditions survive and remain relevant: they stay practical. Vaquero techniques haven't been preserved in amber as historical artifacts. They've been continuously used and adapted because they work. The fact that modern ranchers still use these techniques 500 years after they were developed is the strongest possible evidence of their effectiveness.

The Visibility of Spanish Heritage: Things You Can Point At

One of the strengths of vaquero legacy is that it's visible and tangible. You can point at things and say, "That comes from vaqueros."

A saddle in a ranch barn? That's vaquero-design. A rope used in a rodeo. That's based on vaquero reata tradition. A horse with spurs? That's continuing vaquero practice. The way a cowboy throws a rope? That's vaquero technique. The words being used? Spanish-origin words. The rodeo events? Adapted from vaquero competitions.

Why This History Matters Now

Understanding that the modern American West is built on Spanish and Mexican vaquero foundations changes how you understand American history and American culture. It complicates the narrative of purely American frontier development. It acknowledges cultural exchange, adaptation, and inheritance.

It also provides a completer and more accurate picture of where American ranching traditions came from. The American cowboy is real, and the skills are impressive. But those skills were learned from vaqueros, adapted and refined through American ranching experience, but fundamentally rooted in Spanish colonial vaquero culture.

Recognizing this doesn't diminish American contributions to ranching culture. It contextualizes them. It shows how Americans took an existing tradition and adapted it to new conditions and new scales. That's a legitimate cultural achievement. But it's one that's built on foundations that were already there.

The Series Comes Full Circle

We started this series by asking: how did vaqueros become cowboys? How did Spanish ranching tradition become American Western culture?

The answer is: vaqueros didn't become cowboys. Rather, American settlers encountered vaqueros, learned from them, adopted their techniques and equipment, and then created a new cultural identity that incorporated vaquero tradition while claiming to be distinctly American.

Some of this was conscious learning and adaptation. Some of it was unconscious cultural absorption. Some of it involved deliberate erasure of credit and origin. Some of it involved genuine innovation built on vaquero foundations.

The result is the modern American West—a culture that is visibly, tangibly, and fundamentally rooted in 500 years of Spanish vaquero tradition, even when that foundation isn't always explicitly acknowledged.

The next time you see a Western movie or image, look for the Spanish influences. Notice the saddles, the equipment, the vocabulary, the techniques. Notice how thoroughly vaquero culture has been woven into American Western identity.

The vaquero legacy isn't hidden. It's in plain sight. It's just waiting for someone to notice it.