The Soul of Mexico: A Journey Through Time and Taste

From the ancient milpas of Mesoamerica to the bustling taquerías of modern Mexico City, Mexican cuisine tells a story that spans thousands of years—a narrative woven through corn masa, chile peppers, and the loving hands of countless generations. This is not merely a history of Mexican food; it's the evolution of Mexican cuisine through the lens of family kitchens, where recipes become love letters passed from grandmother to granddaughter, and where every meal connects us to the soul of a nation.

From the ancient milpas of Mesoamerica to the bustling taquerías of modern Mexico City

Ancient Foundations: Where the Story Begins

The history of Mexican food begins in the misty dawn of civilization, around 7000 BCE, when the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica first cultivated the sacred trinity that would define their cuisine forever: corn, beans, and squash—known as the "Three Sisters." The Olmecs, Maya, and later the Aztecs built their entire culinary universe around these foundational ingredients.

In the pre-Columbian world, corn wasn't just food—it was life itself. The Maya believed that the first humans were crafted from corn dough, and women would blow softly on maize before adding it to the cooking pot so it would not "fear the fire". This reverence for corn manifested in the ancient technique of nixtamalization, where dried corn was soaked in lime water to increase its nutritional value and create the masa that would become tortillas and tamales.

Imagine walking through the great market of Tenochtitlan, where thousands of Aztecs traded foods that would be exotic to European eyes: tomatoes, avocados, vanilla, chocolate, and dozens of varieties of chile peppers. The Aztec diet was surprisingly sophisticated, featuring everything from turkey and duck to edible flowers and insects, all seasoned with an array of herbs and spices that gave depth to their culinary traditions.

The tianguis of Tenochtitlán was a market of amazing diversity.

The Sacred Tools of Tradition

Even today, Mexican food stories are inseparable from the tools that have remained unchanged for millennia. The metate, a three-legged stone slab used for grinding corn and spices, still sits in Mexican kitchens as it did in ancient times. The molcajete, a volcanic stone mortar and pestle, continues to be the vessel where salsas come alive through the marriage of tomatoes, chiles, and herbs.

These tools carry more than function—they carry memory. Each scratch on a metate tells a story of countless tortillas, each stain on a molcajete whispers of family recipes refined over generations. As one contemporary chef explains, "How we treat corn, cooking it with lime and grinding it with a mortar and pestle, then hand-cranking it through a machine to produce tortillas, is emulating the process from pre-Hispanic times".

The Great Transformation: When Worlds Collided

The arrival of Spanish conquistadors in 1519 marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of Mexican cuisine. What followed was not a simple replacement of one culinary tradition with another, but rather a complex dance of ingredients, techniques, and flavors that would create something entirely new.

The Spanish brought with them livestock that would transform Mexican protein sources forever: cattle, pigs, chickens, and goats. They introduced dairy products, wheat, rice, olive oil, and spices like cumin and cinnamon. But perhaps most importantly, they brought new cooking techniques, including frying in oil and baking in ovens—methods that were unknown in the pre-Columbian world.

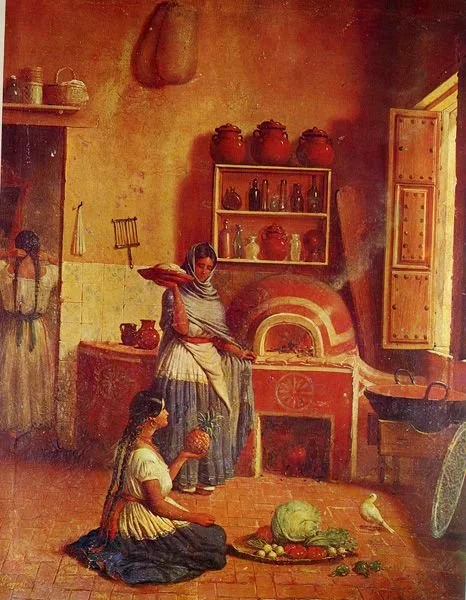

Yet this transformation was not without resistance and adaptation. Indigenous cooks, particularly the women who managed colonial kitchens, became the architects of fusion. In the convents of New Spain, nuns worked alongside indigenous women to create dishes that would become the foundation of Mexican cuisine as we know it today. It was in these kitchens that mole was born—a complex sauce that married indigenous ingredients like chocolate and chiles with European spices and techniques.

Spanish colonial kitchens in mexico from the 1500s.

The Language of Love: Family Recipes and Generational Knowledge

In Mexican culture, recipes are rarely written down. Instead, they live in the hands of the cook, passed down through what food anthropologists call "embodied knowledge". "In general, Mexican traditions are still passed down verbally and informally, which makes them ever-changing rituals with new additions and omissions by each generation".

This oral tradition creates something profound: each family's version of a dish becomes a unique fingerprint of their history. The mole that tastes like home is never quite the same as the one from the neighboring house, because it carries the memory of different hands, different stories, different adaptations born from love and necessity. Text continues after popular blog posts section below.

Popular Blog Posts:

The Heartbeat of Identity: Food as Cultural Expression

Mexican cuisine is more than sustenance—it's a form of cultural expression recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This recognition acknowledges that traditional Mexican cuisine is "a comprehensive cultural model comprising farming, ritual practices, age-old skills, culinary techniques and ancestral community customs and manners".

The role of food in Mexican identity extends far beyond the kitchen. During Day of the Dead celebrations, families prepare elaborate meals for their ancestors, believing that the aromas of favorite dishes will guide spirits home. Tamales become offerings, mole becomes a bridge between worlds, and chocolate returns to its sacred roots as a drink worthy of the gods.

This spiritual dimension of food reveals itself in countless ways. The colors of chiles en nogada—green poblano peppers, white walnut sauce, and red pomegranate seeds—mirror the Mexican flag, making the dish a edible symbol of national pride. Mole, Mexico's national dish, represents the country's complex history in every spoonful, blending indigenous cacao with European spices in a sauce that can take days to prepare and represents the marriage of two worlds.

The Evolution Continues: Modern Mexican Cuisine

As Mexico entered the 20th century, the evolution of Mexican cuisine accelerated. The rise of street food culture democratized flavors that had once been reserved for special occasions. Tacos, tamales, and quesadillas became the people's food, sold from carts and stands throughout the country.

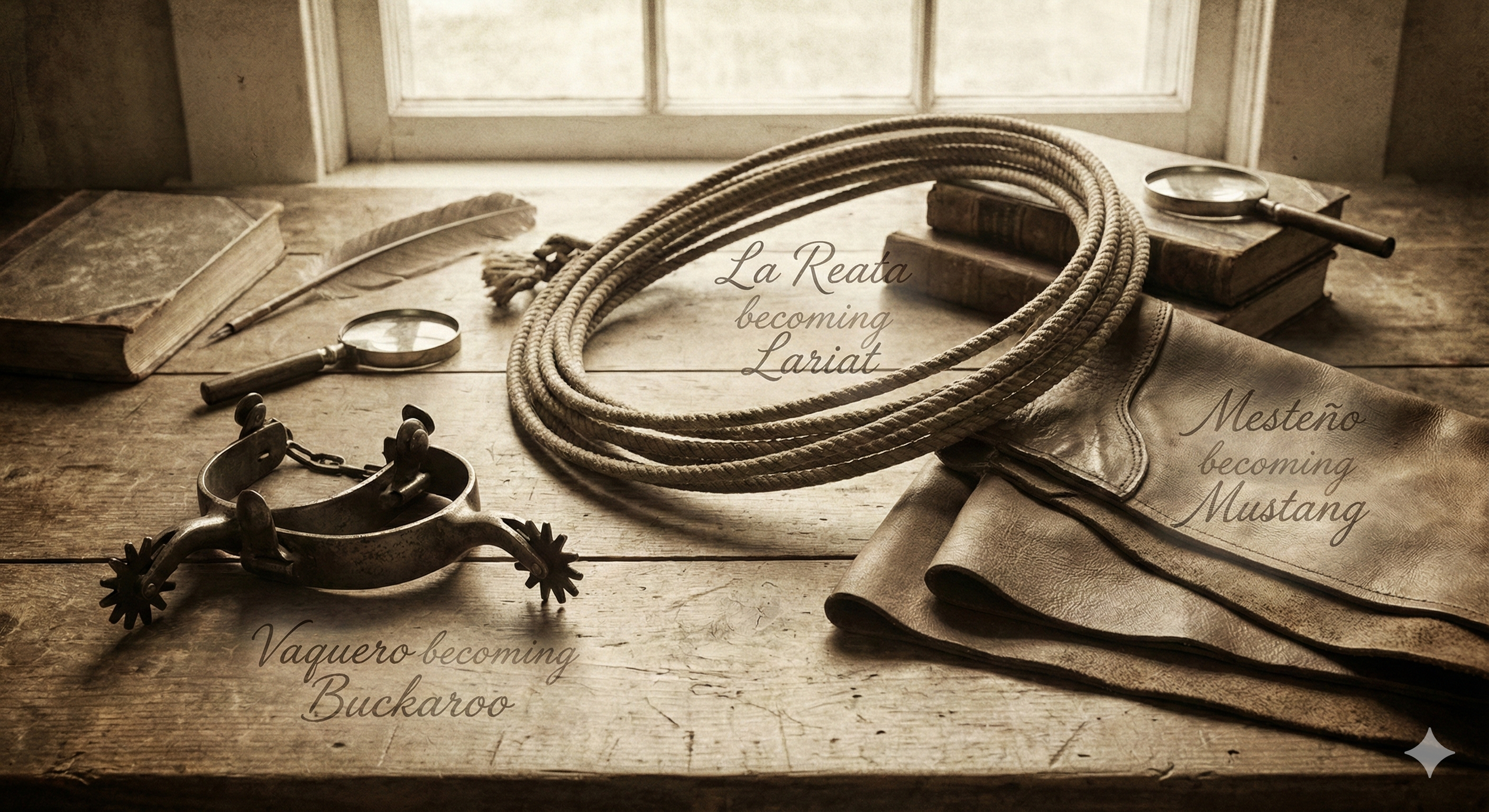

The globalization of Mexican food in the latter half of the 20th century brought both opportunities and challenges. While dishes like tacos and burritos became beloved worldwide, they often lost their authenticity in the process of commercialization. The rise of Tex-Mex cuisine, while delicious in its own right, created confusion about what constituted "authentic" Mexican food.

Mexican food has had global impact.

Yet this period also saw a renaissance of interest in regional Mexican cuisines. Chefs began exploring the distinct flavors of different states—the complex moles of Oaxaca, the seafood traditions of Veracruz, the Mayan-influenced dishes of Yucatán. This movement toward regional authenticity helped preserve traditional techniques and ingredients that might otherwise have been lost.

Contemporary Challenges and Innovations

Today's Mexican cuisine faces new challenges and opportunities. The farm-to-table movement has encouraged Mexican chefs to rediscover heirloom varieties of corn and forgotten vegetables. Traditional techniques like nixtamalization are experiencing a revival as chefs recognize their nutritional and cultural importance.

Modern Mexican restaurants are elevating street food to fine dining levels while maintaining their essential character. Birria, a traditional stew from Jalisco, has become a social media sensation, sparking interest in regional Mexican dishes among younger generations.

The rise of plant-based eating has also influenced Mexican cuisine, with many traditional dishes naturally fitting into vegetarian and vegan diets. Beans, corn, and vegetables have always been central to Mexican cooking, making the cuisine naturally adaptable to contemporary dietary preferences.

The Threads That Bind: Food as Cultural Continuity

What makes Mexican cuisine extraordinary is not just its flavors, but the way it maintains continuity across time and space. A tortilla made today follows the same basic process used by the Aztecs centuries ago. The rhythm of grinding corn on a metate connects contemporary cooks to their ancestors in an unbroken chain of tradition.

This continuity is preserved through the Mexican food stories that accompany each recipe. When a grandmother teaches her granddaughter to make tamales, she's not just sharing a recipe—she's passing on a piece of cultural DNA. The stories that accompany the cooking process—tales of feast and famine, celebration and sorrow, immigration and adaptation—become as important as the ingredients themselves.

These stories create what food anthropologists call "culinary identity"—a sense of belonging that transcends geographical boundaries. Mexican immigrants carrying their food traditions to new countries don't just maintain their cuisine; they create bridges between cultures, introducing new flavors while adapting to local ingredients and tastes.

The Future of Mexican Cuisine

As we look toward the future, the evolution of Mexican cuisine continues to unfold. Young Mexican chefs are experimenting with molecular gastronomy techniques applied to traditional dishes, creating innovative presentations that honor ancestral flavors while pushing culinary boundaries.

The growing interest in sustainability has led to renewed appreciation for traditional farming methods like chinampas (floating gardens) and milpas (polyculture farming systems) that have sustained Mexican agriculture for centuries. These ancient techniques are being rediscovered as solutions to modern environmental challenges.

Food tourism has brought international attention to regional Mexican cuisines, creating economic opportunities for traditional cooks while raising awareness of Mexico's culinary diversity. This attention has helped preserve endangered dishes and techniques that might otherwise have been lost to modernization.

The Eternal Feast

Mexican cuisine is ultimately a story of resilience, adaptation, and love. From the ancient reverence for corn to the contemporary celebration of street food, from the sacred cacao of the Aztecs to the modern mole of Oaxaca, every dish tells a chapter in the ongoing narrative of Mexican culture.

The history of Mexican food is not just about ingredients and techniques—it's about the human stories that give those ingredients meaning. It's about the grandmother who wakes at dawn to prepare masa for her family's breakfast, the street vendor who carries on his father's recipe for the perfect taco, the chef who honors ancient traditions while creating something new.

In every Mexican kitchen, whether in a humble home or a celebrated restaurant, the same magic happens: ingredients are transformed not just by heat and technique, but by love, memory, and the weight of history. This is the true soul of Mexican cuisine—not just the food itself, but the connections it creates between past and present, between family and community, between the sacred and the everyday.

As we savor the complex flavors of Mexican cuisine, we taste more than food—we taste the essence of a civilization that has learned to honor its past while embracing its future, creating a culinary legacy that will nourish both body and soul for generations to come.