The Ultimate Guide to Traditional Mexican Dishes

Authentic Flavors from Mexico’s Rich Culinary Heritage

Mexican cuisine is a vibrant tapestry woven from thousands of years of indigenous tradition, Spanish colonial influence, and regional adaptation. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, traditional Mexican dishes are more than just food—they are a living expression of history, community, and identity. This guide explores the origins, techniques, ingredients, and cultural significance of Mexico’s most iconic dishes, offering a comprehensive resource for anyone seeking to understand and savor authentic Mexican food.

What Defines Traditional Mexican Dishes?

Traditional Mexican dishes are rooted in indigenous ingredients and cooking methods that predate Spanish colonization. The foundation of this cuisine is built on three essential ingredients: corn (maize, beans (frijoles), and chiles. These staples, first cultivated by ancient civilizations like the Olmecs and Mayans, form the backbone of countless recipes and distinguish authentic Mexican food from modern adaptations.

Key characteristics of traditional Mexican dishes:

Emphasis on fresh, whole ingredients, often sourced locally or grown in home gardens.

Use of time-honored techniques such as nixtamalization (alkaline corn treatment), molcajete grinding (stone mortar and pestle), and comal cooking (flat griddle).

Reliance on corn tortillas over flour, especially in central and southern regions.

Minimal use of processed cheeses; instead, fresh cheeses like queso fresco and Oaxaca cheese are favored.

Complex interplay of indigenous and Spanish influences, resulting in dishes that are both rustic and sophisticated.

Deep respect for seasonality, with many dishes tied to specific harvests or religious festivals.

Communal preparation, especially for labor-intensive foods like tamales and mole, reinforcing family and community bonds.

The Most Important Traditional Mexican Dishes

Mole Poblano: Mexico’s National Culinary Treasure

Mole poblano is often called the national dish of Mexico. Originating in Puebla, this complex sauce can contain up to 100 ingredients, including various chiles, chocolate, spices, nuts, and dried fruits. Mole exemplifies the fusion of pre-Columbian and Spanish influences, combining indigenous cacao and chiles with colonial almonds and spices.

Preparation is labor-intensive, requiring careful toasting, grinding, and blending to achieve its signature depth and richness. Traditionally served over chicken or turkey, mole poblano is a celebratory dish reserved for special occasions

There are at least eight recognized types of mole, each with unique flavor” profiles and regional variations, such as mole negro, mole verde, and mole coloradito, especially in Oaxaca, known as the “land of the seven moles”.

The process of making mole can take several days, with each ingredient toasted and ground separately before being combined. Mole is often topped with sesame seeds and served with rice, tortillas, and sometimes plantains.

Family mole recipes are closely guarded secrets, passed down through generations, and often prepared for weddings, baptisms, and major holidays.

Chiles en Nogada: The Patriotic Masterpiece

Chiles en nogada holds a special place in Mexican culture, especially during September’s Independence Day celebrations. Created by nuns in Puebla in 1821, this dish features poblano chiles stuffed with a sweet-savory picadillo, covered in a walnut cream sauce, and garnished with pomegranate seeds. The green, white, and red colors mirror the Mexican flag, making it both a culinary and patriotic symbol. Its preparation is seasonal, relying on fresh walnuts and pomegranates, and is a cherished annual tradition.

The picadillo filling typically includes ground meat, dried fruits, nuts, and spices, creating a complex balance of flavors. The walnut sauce (nogada) is made from freshly shelled walnuts, milk, and sherry, and must be prepared just before serving to preserve its creamy texture and delicate flavor. Chiles en nogada is often enjoyed with a glass of Mexican white wine or agua fresca to complement its richness. The dish is a symbol of national pride and is featured in festivals, parades, and family gatherings throughout Mexico in September.

Pozole: Ancient Ceremonial Stew

Pozole is one of Mexico’s oldest dishes, with roots in Aztec ceremonial feasts. This hearty soup features hominy (nixtamalized maize kernels) in a rich broth, traditionally made with pork. There are three main varieties:

Pozole Rojo (red): made with guajillo or ancho chiles.

Pozole Verde (green): with tomatillos and green chiles.

Pozole Blanco (white): without chile additions.

Pozole is served with garnishes like diced onion, sliced radishes, oregano, lime, and chile piquín, making it an interactive and communal dining experience. Pozole is often prepared for large gatherings, such as birthdays, weddings, and national holidays, due to its ability to feed many people. The dish is traditionally accompanied by tostadas, avocado, and crema. In some regions, chicken or seafood is used instead of pork, and vegetarian versions are gaining popularity. The ritual of serving pozole includes passing around bowls of garnishes, allowing each guest to customize their bowl.

Tamales: Portable Ancient Nutrition

Tamales showcase the ingenuity of ancient Mexican civilizations. Masa (corn dough) is filled with savory meats, chiles, or sweet fruits, then wrapped in corn husks or banana leaves and steamed. Regional variations abound, from Oaxacan tamales in banana leaves to sweet tamales with raisins and pineapple. Tamale-making is often a communal activity, especially during Christmas, symbolizing family unity and tradition.

Tamales are made in hundreds of varieties across Mexico, with fillings ranging from mole, rajas (chile strips), and cheese to sweetened masa with cinnamon and fruit. The process of making tamales, called a “tamalada,” is a social event where families gather to prepare dozens or even hundreds of tamales at once. Tamales are eaten year-round but are especially important during holidays like Christmas, Día de la Candelaria, and Día de los Muertos. In Veracruz, tamales can be as large as a loaf of bread and are often filled with pork and wrapped in banana leaves for extra moisture and flavor.

Regional Diversity in Traditional Mexican Cuisine

Northern Mexico: Beef and Flour Traditions

Northern Mexican cuisine reflects the region’s cattle ranching heritage and wheat cultivation. Dishes like carne asada (grilled beef), flour tortillas, and cabrito (young goat) are staples. The proximity to the United States and unique climate conditions have created a cuisine distinct from central Mexico’s corn-based traditions. The region is famous for its cheeses, such as queso menonita and asadero, and for hearty dishes like machaca (dried, shredded beef) and burritos. Baja California, part of the north, is renowned for its seafood, especially fish tacos and ceviche, and is home to Mexico’s oldest wine region. Grilling (asado) is the preferred cooking method, and marinades often include citrus, garlic, and chiles for deep flavor. Wheat flour tortillas are more common than corn, and are used for burritos, quesadillas, and other regional specialties.

Central Mexico: The Heart of Culinary Complexity

Central Mexico, home to the ancient Aztec empire, is known for its elaborate moles and sophisticated cooking techniques. Dishes from Puebla and Oaxaca, such as mole negro and tlayudas, showcase the region’s culinary artistry and preservation of pre-Columbian methods. Mexico City is a melting pot of regional cuisines, with street foods like tacos al pastor, tlacoyos, and sopes widely available.

The region is also known for barbacoa (pit-roasted meats), carnitas (slow-cooked pork), and a wide variety of tamales. Central Mexican cuisine makes extensive use of fresh herbs like epazote and cilantro, and features both indigenous and Spanish ingredients. Street food culture is vibrant, with markets offering everything from quesadillas to atole (corn-based hot drink).

Yucatán Peninsula: Mayan Culinary Legacy

Yucatecan cuisine maintains strong Mayan influences, featuring dishes like cochinita pibil (pork cooked in banana leaves) and unique ingredients such as achiote, sour oranges, and habanero chiles. The tropical climate allows for different crops, resulting in a cuisine distinct from the rest of Mexico. Cochinita pibil is marinated in achiote and citrus, wrapped in banana leaves, and slow-roasted in an underground oven (píib), resulting in tender, flavorful meat. Other regional specialties include papadzules (egg-filled tortillas in pumpkin seed sauce), sopa de lima (lime soup), and panuchos (tortillas stuffed with black beans). The use of habanero chiles gives Yucatecan food a distinctive heat, balanced by cooling sides like pickled onions and fresh fruit. The region’s cuisine is heavily influenced by Caribbean and Middle Eastern flavors, due to historical trade and migration.

Coastal Regions: Seafood Abundance

Mexico’s coastal states are renowned for fresh seafood preparations like ceviche, fish tacos, and seafood cocktails. Pacific coast dishes highlight the ocean’s bounty while maintaining traditional Mexican seasoning and preparation methods. Veracruz is famous for its huachinango a la veracruzana (red snapper in tomato, olive, and caper sauce) and arroz a la tumbada (seafood rice). Sinaloa and Nayarit are known for aguachile (shrimp marinated in lime and chile) and zarandeado (grilled fish). Coastal cuisine often features tropical fruits, coconut, and plantains, and is influenced by African, Spanish, and indigenous traditions. Street vendors sell a variety of seafood snacks, including shrimp cocktails, octopus tostadas, and fried fish.

Essential Cooking Techniques

Nixtamalization: The Ancient Corn Process

Nixtamalization is a 3,500-year-old process that involves treating corn with lime water to improve its nutritional value and create masa. This technique increases protein quality, adds calcium, and gives corn tortillas their distinctive flavor and texture. The process removes the hull from corn kernels, making them easier to grind and digest. Nixtamalized corn is used to make masa for tortillas, tamales, and atole. The technique enhances the bioavailability of niacin, preventing nutritional deficiencies like pellagra. Traditional nixtamalization is still practiced in rural areas, with families soaking and grinding corn by hand.

Molcajete Grinding

Using a molcajete (volcanic stone mortar and pestle) creates textures and flavors impossible to achieve with modern equipment. The rough surface releases essential oils from chiles and spices, producing the perfect consistency for salsas and spice pastes. The molcajete is used to grind garlic, chiles, tomatoes, and herbs for salsas, guacamole, and spice rubs. Grinding by hand allows for better control of texture and flavor, and is considered a meditative, communal activity. The metate, a larger stone slab, is used for grinding corn and cacao. Many families pass down their molcajetes as heirlooms, believing that the stone absorbs the flavors of generations.

Comal Cooking

A comal is a flat clay or metal griddle used for cooking tortillas, roasting chiles, and charring vegetables. This technique concentrates flavors through controlled charring while preserving the ingredients’ structural integrity. Comals are used to toast spices, dry roast tomatoes and tomatillos for salsas, and heat tortillas. The comal imparts a subtle smokiness and enhances the aroma of ingredients. In rural areas, comals are often placed over wood fires, adding another layer of flavor. Modern kitchens use cast iron or steel comals, but traditional clay comals are still prized for their even heat distribution.

Other Traditional Techniques

Barbacoa: Slow-cooking meats in underground pits, often wrapped in agave or banana leaves, resulting in tender, flavorful dishes like barbacoa de borrego (lamb) and cochinita pibil.

Clay Pot Cooking: (Cazuela):Used for stews, beans, and moles, clay pots retain heat and moisture, enhancing the depth of flavor.

Dry Roasting: Chiles, spices, and seeds are often dry-roasted to intensify their flavors before being ground or blended.

Steaming: Essential for tamales and some seafood dishes, steaming preserves moisture and delicate flavors.

The Holy Trinity: Corn, Beans, and Chiles

Corn (Maíz): The foundation of Mexican cuisine, providing up to 80% of calories in traditional diets. Used for tortillas, tamales, atole, and more. Beans (Frijoles): Essential proteins, featured in countless preparations from simple boiled beans to complex refried variations. Varieties include black, pinto, and flor de mayo beans. ChilesOver 200 varieties grown in Mexico, providing not just heat but complex flavors and vibrant colors. Common types include jalapeño, poblano, ancho, guajillo, and habanero. Chiles are used fresh, dried, roasted, or smoked, each form imparting unique flavors. Beans are often cooked with herbs like epazote for added flavor and digestibility. Corn is also used to make drinks like atole and champurrado, and snacks like elote (grilled corn on the cob).

Indigenous Vegetables, Fruits, Herbs, and Spices

Vegetables: Tomatillos, nopales (cactus pads), quelites (wild greens), and squash are staples, often featured in soups, stews, and salads.

Fruits: Guavas, papayas, mamey, and a variety of tropical fruits are used both fresh and in cooking, especially in desserts and beverages. Fruits like prickly pear (tuna) and sapote are used in both sweet and savory dishes.

Herbs: Epazote, hierba santa, and Mexican mint marigold impart distinctive flavors, especially in bean dishes and moles.

Spices: Mexican oregano, canela (Mexican cinnamon), and various chile powders create complex seasoning profiles. Allspice, cloves, and cumin are also common. Many indigenous herbs have medicinal properties, such as epazote for digestion and hierba santa for respiratory health. The use of fresh herbs and spices is a hallmark of Mexican home cooking, with families often growing their own in kitchen gardens.

The Cultural Significance of Traditional Mexican Food

Family and Community Bonds

The preparation of complex dishes like mole or tamales is often a communal effort, fostering knowledge transfer between generations and strengthening family ties. Food is central to family gatherings, celebrations, and religious observances. Cooking together is a way to teach children about heritage, values, and culinary skills. Recipes are often unwritten, passed down orally and through demonstration. Community events, such as fiestas and religious festivals, revolve around shared meals and traditional foods.

Religious and Ceremonial Importance

Many dishes are tied to specific holidays and life events:

Tamales for Christmas and Día de la Candelaria.

Rosca de Reyes for Three Kings Day.

Special preparations for Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), such as pan de muerto and sugar skulls.

Food offerings (ofrendas) are made to honor ancestors during Día de los Muertos, with favorite dishes and drinks placed on altars.

Weddings, baptisms, and quinceañeras feature elaborate feasts, often including mole, barbacoa, and tamales.

Each region has its own culinary traditions for major holidays, reflecting local ingredients and customs.

Preservation of Indigenous Knowledge

Traditional Mexican cuisine preserves ancient agricultural practices, food preparation techniques, and nutritional wisdom, representing thousands of years of culinary evolution and environmental adaptation. Heirloom varieties of corn, beans, and chiles are still cultivated using traditional methods. Knowledge of wild edible plants and foraging is passed down in rural communities.Culinary traditions are a source of pride and identity, especially among indigenous groups.

Health Benefits of Traditional Mexican Cuisine

When prepared authentically, traditional Mexican dishes offer exceptional nutritional profiles: The combination of corn and beans creates complete proteins. Chiles provide antioxidants and vitamins. Nixtamalization increases bioavailable nutrients. Indigenous ingredients like chiles and epazote have documented medicinal properties, such as anti-inflammatory effects and digestive benefits. Many traditional dishes are naturally gluten-free and high in fiber. The use of fresh vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats (like avocado) supports heart health and balanced nutrition. Traditional diets have been linked to lower rates of chronic diseases in rural Mexican communities.

Modern Adaptations and Ingredient Sourcing

Adapting for Contemporary Diets

Many traditional dishes have been adapted for vegetarian, vegan, and gluten-free diets. For example: vegetarian tamales use beans, cheese, or vegetables as fillings. Gluten-free tortillas are made from 100% corn masa. Plant-based pozole substitutes mushrooms or jackfruit for pork. Vegan versions of mole and enchiladas use plant-based proteins and dairy alternatives. Health-conscious cooks reduce lard and salt, using olive oil and fresh herbs for flavor. Mexican cuisine is highly adaptable, with new recipes emerging to meet dietary needs without sacrificing authenticity.

Sourcing Authentic Ingredients

Finding authentic Mexican ingredients outside of Mexico can be challenging. Try visiting Latin American grocery stores for fresh chiles, masa harina, and specialty herbs. Shopping online for hard-to-find spices and dried chiles. Growing herbs like epazote or cilantro at home for freshness. Many supermarkets now carry Mexican staples like tomatillos, nopales, and queso fresco. Farmers’ markets may offer heirloom varieties of corn and beans. Community gardens and seed exchanges help preserve traditional crops and flavors.

Holiday and Seasonal Dishes

Mexican cuisine is closely tied to the calendar, with special dishes marking each season and celebration:

Día de los Muertos: Pan de muerto, mole, and sugar skulls.

Christmas: Tamales, bacalao (salted cod), and ponche (fruit punch).

Independence Day: Chiles en nogada, pozole, and patriotic desserts.

Easter: Capirotada (bread pudding) and meatless dishes.

Las Posadas: (December) features atole, buñuelos (fried dough), and tamales.

Lent and Holy Week: inspire meatless dishes like tortas de camarón (shrimp patties) and romeritos (greens in mole). Regional variations abound, with each state offering unique holiday specialties.

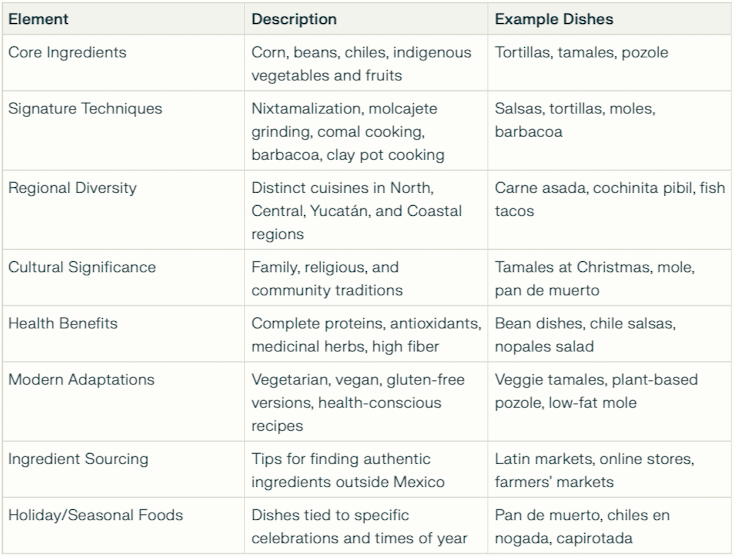

Key Elements of Mexican Cuisine

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What makes mole authentic?

Authentic mole is defined by its complex layering of flavors, use of indigenous and colonial ingredients, and traditional preparation methods that can take days to complete. Each family and region has its own version, with unique spice blends and techniques.

How do you make traditional tortillas?

Traditional tortillas are made from nixtamalized corn, ground into masa, shaped by hand or with a press, and cooked on a comal. The process is simple but requires skill to achieve the perfect texture and flavor.

What’s the difference between Mexican and Tex-Mex food?

Mexican food emphasizes corn, fresh chiles, and indigenous techniques, while Tex-Mex often uses flour tortillas, yellow cheese, and Americanized flavors. Tex-Mex is a regional adaptation that blends Mexican and American ingredients and tastes.

Are there gluten-free options in traditional Mexican cuisine?

Yes, most traditional dishes—such as corn tortillas, tamales, and pozole—are naturally gluten-free. Wheat is more common in northern Mexico, but corn remains the staple in most regions.

Personal and Cultural Stories

Many families have recipes passed down through generations, each with unique touches and stories. For example, a grandmother’s mole recipe might include a secret blend of chiles, or a family’s tamale tradition could involve a day-long gathering to prepare dozens of varieties. These stories add depth and meaning to the food, connecting people to their roots and to each other. Oral storytelling and cooking demonstrations are essential for preserving culinary heritage. Food is often used to mark life’s milestones, from baptisms to funerals, with each event featuring specific dishes. Regional pride is strong, with families and communities celebrating their unique culinary contributions to Mexican cuisine.