Cultural and Social Importance of Traditional Mexican Food

Mexican food culture represents far more than simple sustenance—it serves as a powerful thread that weaves together the fabric of community, family, and cultural identity across generations. This rich culinary tradition stands as a testament to the enduring power of food to preserve heritage, strengthen social bonds, and maintain connections to ancestral wisdom.

THE FOUNDATION OF MEXICAN FOOD CULTURE

Traditional Mexican cuisine encompasses a comprehensive cultural model that includes farming practices, ritual ceremonies, ancient skills, and community customs. This culinary tradition is built upon three fundamental pillars: corn, beans, and chili peppers—ingredients that have sustained Mexican communities for more than 9,000 years. Corn in particular is considered sacred in many Indigenous belief systems, viewed as a gift from ancestors rather than merely a crop. The ancient process of nixtamalization, which turns dried corn into masa through alkaline treatment, illustrates how cooking techniques passed down for centuries enhance both flavor and nutritional value.

FAMILY RITUALS AND FOOD TRADITIONS

Mexican family rituals centered around food serve as powerful mechanisms for cultural transmission and family bonding. Preparing traditional dishes often becomes a multigenerational affair, with elders teaching children and grandchildren the intricate techniques that produce authentic flavors. One iconic example is the tamalada, a tamale-making gathering that can last an entire day. Family members chat, laugh, sing, and share stories while spreading corn dough on husks and filling each packet with meats, chilies, or sweet fruits. These events reinforce familial ties while ensuring that recipes, stories, and preparation methods endure.

Pozole Sundays offer another vivid illustration. Across many regions, families simmer hominy with pork, chilies, and aromatics in large pots all morning so that by lunchtime an aromatic stew invites everyone to the table. Beyond nourishment, these standing Sunday gatherings offer space for news, advice, and affection, anchoring extended relatives to a shared rhythm of life.

COMMUNITY GATHERINGS AND SOCIAL COHESION

Food and community in Mexico are inseparable. Local street markets, or tianguis, act not only as commercial hubs but also as informal town squares where neighbors check in on one another, discuss politics, and celebrate shared heritage. During annual patron-saint festivals, neighborhoods collaborate in preparing massive communal meals—birria in Jalisco, cochinita pibil in Yucatán, barbacoa in Hidalgo—setting up long rows of tables so that anyone can sit, eat, and socialize. The practice illustrates the cultural notion of “familismo,” which elevates community solidarity to the level of kinship.

At the tianguis or Mexican market

RELIGIOUS CELEBRATIONS AND SPIRITUAL CONNECTIONS

Traditional Mexican celebrations intertwine cuisine and spirituality. The Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos) bridges earthly and ancestral realms through food. Families construct ofrendas—domestic altars laden with pan de muerto, sugar skulls, mole, and cups of atole next to snapshots of deceased relatives. The aromas are said to guide spirits home, turning the household kitchen into a sacred conduit for remembrance.

Christmas season centers on Las Posadas, nine nights of neighborhood processions reenacting Mary and Joseph’s search for shelter. Hosts welcome pilgrims with buñuelos, champurrado, and tamales. These foods symbolize hospitality, humility, and gratitude, converting everyday ingredients into devotional offerings. Similarly, Quinceañera banquets featuring mole poblano and arroz rojo celebrate a young woman’s passage to adulthood, aligning personal milestones with collective culinary pride.

PRESERVATION OF INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE

Mexican cuisine operates as a living archive of Indigenous agricultural wisdom. In Oaxaca’s Mixteca region, farmers still nurture ancestral land-races of corn in milpa fields—a symbiotic planting of maize, beans, and squash that enriches soil and diversifies diets. Along Lake Xochimilco, chinampa “floating gardens” pioneered by the Mexica continue to yield spinach, cilantro, and edible flowers without synthetic inputs.

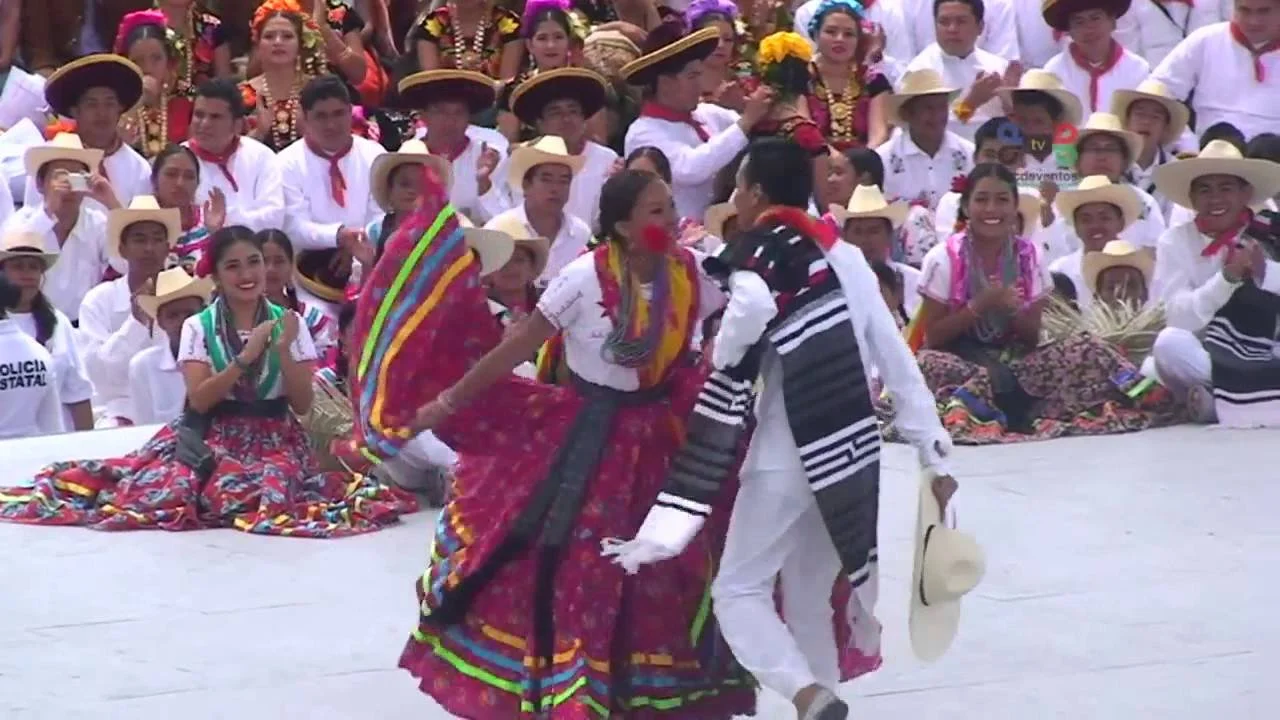

Traditional dance of the Mixteca

Traditional tools also endure. Clay pots (ollas) impart earthy perfume to beans, while molcajetes (volcanic-stone mortars) coax essential oils from roasted chilies. Fermented drinks such as pulque, tepache, and tesgüino preserve carbohydrates in probiotic form, reflecting sophisticated pre-Columbian understandings of nutrition and microbiology.

MODERN CHALLENGES AND CULTURAL RESILIENCE

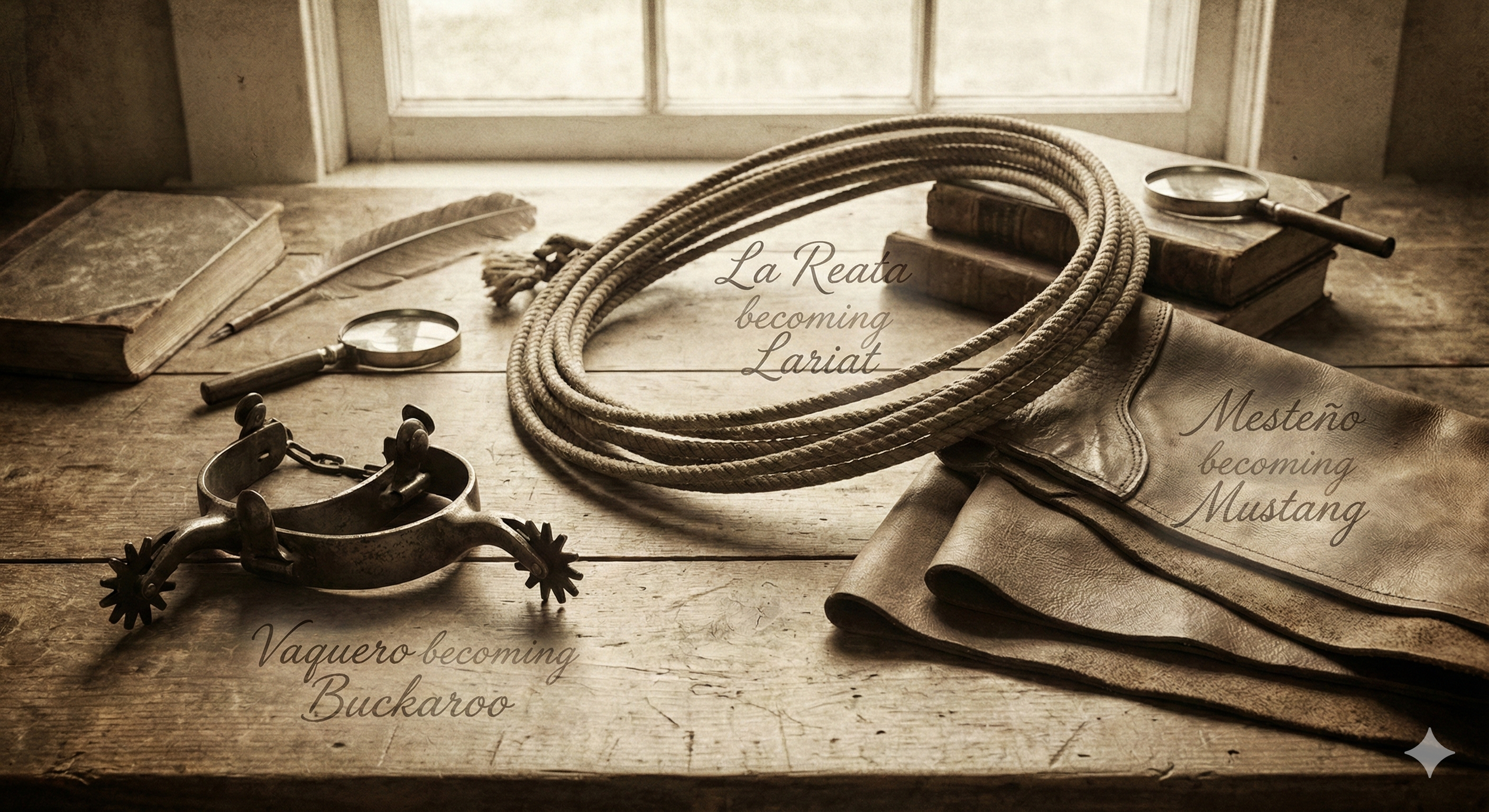

Globalization, convenience foods, and migration have challenged traditional foodways, yet Mexican cuisine remains remarkably resilient. Urban cooks post family recipes on social media, sustaining intergenerational dialogue even when relatives live apart. Food trucks and pop-ups run by Mexican immigrants transform city blocks in Los Angeles or Chicago into sites of cultural exchange, where customers learn Indigenous terminology like huitlacoche or mixiote while eating.

Government-sponsored seed banks now collaborate with Indigenous custodians to protect heirloom varieties of blue corn or chilhuacle chili. Farmers’ cooperatives market these heritage crops as premium products, turning cultural preservation into economic opportunity.

THE COMMUNAL ASPECT OF MEXICAN MEALS

A typical Mexican table emphasizes sharing: baskets of warm tortillas, bowls of salsa, and platters of grilled meats are placed in the middle for everyone to assemble their own tacos. After the last bite, conversation often lingers in a cherished ritual called sobremesa, during which family members discuss politics, gossip, or dreams for the future. Researchers link such practices to higher levels of psychological well-being, stronger family identity, and even lower rates of adolescent substance abuse. In Mexico, relationship-building is not separate from nourishment; it is part of the meal itself.

Hungry?

THE SACRED RECOGNITION OF MEXICAN CULINARY HERITAGE

In 2010, traditional Mexican cuisine achieved unprecedented global recognition when UNESCO inscribed it on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This historic designation placed Mexican gastronomy alongside French cuisine as one of only two national cuisines to receive such an honor, acknowledging its profound cultural significance that extends far beyond mere sustenance.

The UNESCO recognition specifically emphasized that traditional Mexican cuisine represents a comprehensive cultural model comprising farming practices, ritual ceremonies, ancient skills, culinary techniques, and ancestral community customs. This acknowledgment highlighted the sophisticated system underlying Mexican food culture, where collective participation in the entire food chain—from planting and harvesting to cooking and eating—creates a living cultural practice that expresses community identity and reinforces social bonds.

The designation focused particularly on the culinary traditions of Michoacán state, recognizing how these practices serve as a paradigm for understanding the broader cultural importance of Mexican cuisine. Gloria López of Mexico’s National Council of Culture and Arts emphasized that this recognition went beyond taste, representing the protection of an ancestral way of life that has sustained communities for millennia.

Mexico boasts 35 UNESCO World Heritage Sites , the most in North America.

STREET FOOD AS CULTURAL EXPRESSION

Mexican street food culture represents one of the most dynamic and accessible expressions of the country’s culinary heritage. Over 75 percent of Mexico City’s population consumes street food at least once weekly, demonstrating how these portable meals have become integral to daily life rather than merely convenient alternatives. This phenomenon reflects the deep historical roots of Mexican street food, which traces back to ancient Aztec marketplaces known as tianguis, where vendors sold prepared foods to workers and travelers.

Street food vendors, known as puesteros, create vibrant social gathering spaces that function as community hubs where people from diverse backgrounds converge to share meals and conversations. These informal dining spaces foster social cohesion by breaking down economic and social barriers, allowing construction workers, office employees, students, and tourists to sit side by side enjoying the same authentic flavors.

The cultural significance of street food extends beyond mere commerce—it serves as a platform for showcasing regional diversity and preserving traditional recipes. Each region’s street food reflects local ingredients, cooking techniques, and cultural preferences, creating a living map of Mexico’s culinary geography. From the seafood-centric dishes of coastal areas to the meat-heavy preparations of northern states, street food vendors maintain and transmit regional knowledge while adapting to urban environments.

TRADITIONAL MARKETS AS CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS

Mexican traditional markets, or mercados, represent far more than commercial spaces—they function as cultural institutions that preserve and transmit culinary knowledge across generations. These markets, with roots extending back to pre-Columbian tianguis, continue to serve as vital centers for food distribution, cultural exchange, and community interaction.

The tianguis system, which operates on specific days of the week, maintains connections to ancient trading practices while adapting to modern needs. These temporary markets create recurring opportunities for rural producers to connect directly with urban consumers, preserving traditional agricultural practices and supporting local economies. The system demonstrates remarkable resilience, having survived colonization, industrialization, and globalization while maintaining its essential character.

Modern Mexican markets serve multiple functions beyond food distribution. They operate as informal universities where culinary knowledge is transmitted through observation and practice. Young vendors learn traditional preparation methods by working alongside experienced cooks, while customers acquire knowledge about seasonal ingredients, cooking techniques, and cultural practices through casual interactions. This organic educational system ensures that traditional knowledge remains alive and accessible to new generations.

SEASONAL CELEBRATIONS AND FOOD TRADITIONS

Mexican food culture follows a sophisticated seasonal calendar that aligns culinary practices with religious observances, agricultural cycles, and cultural celebrations. From September through February, Mexico experiences its most intensive period of food-centered celebrations, beginning with Independence Day and extending through Día de la Candelaria.

The autumn season introduces chiles en nogada, a complex dish that requires poblano peppers, walnut cream sauce, and pomegranate seeds to create the colors of the Mexican flag. This elaborate preparation demonstrates how Mexican cuisine transforms seasonal ingredients into powerful cultural symbols that reinforce national identity during independence celebrations.

October brings dulce de calabaza, candied pumpkin prepared with cinnamon, cloves, and piloncillo that appears in markets and festivals throughout the country. This dessert exemplifies how Mexican food culture adapts to seasonal availability while maintaining traditional preparation methods that have been refined over centuries.

The Christmas season showcases the most elaborate Mexican food traditions, with families preparing complex dishes that require days of preparation and collaborative effort. Traditional Christmas foods include pavo navideño (stuffed turkey), bacalao (cod), romeritos (seepweed), and tamales, each carrying specific cultural significance and requiring specialized knowledge to prepare properly. Text continues after popular blog posts section below.

Popular Blog Posts:

ANSWERS TO COMMON QUESTIONS

What makes Mexican food authentic?

Authenticity rests on traditional ingredients such as native corn, beans, and chili peppers; regional recipes upheld by oral tradition; and preparation techniques—like nixtamalization or slow wood-fire cooking—that remain faithful to Indigenous and mestizo heritage rather than international trends.

How does Mexican food bring families together?

Families regularly gather to prepare dishes that require many hands—tamales, barbacoa, or pozole—transforming kitchens into communal workshops where skills and stories are exchanged. Shared mealtimes and the custom of sobremesa deepen emotional bonds and cultural identity.

Why is Mexican food important to Mexican culture?

It safeguards Indigenous knowledge, marks religious and civic celebrations, and acts as a daily expression of solidarity among relatives and neighbors. Through cuisine, Mexicans reaffirm collective history and pass it lovingly to future generations.

What role does food play in Mexican religious celebrations?

During events such as Día de los Muertos, Christmas posadas, or Quinceañeras, traditional dishes carry symbolic weight: they invite spirits, embody virtues like hospitality, and solemnize life-changing rites.

How do Mexican families preserve food traditions?

They teach children at home, host community cookouts, document recipes on digital platforms, cultivate heirloom seeds, and insist on ingredients purchased from local markets rather than industrial substitutes.

CONCLUSION

Traditional Mexican food is more than a catalog of flavors; it is a sophisticated system of cultural memory, social cohesion, and spiritual meaning. Through family rituals, communal gatherings, religious festivals, and safeguarding of Indigenous ecology, Mexican cuisine sustains identity across centuries. Even in the face of modernization, its adaptive yet faithful spirit continues to nourish bodies and communities, offering a resilient blueprint for preserving heritage while embracing the future.